A Section § 1983 lawsuit permits you to seek financial compensation for violations of your constitutional rights by state and local government officials, such as police officers or prison guards, while they were acting under color of law.

A Section § 1983 lawsuit may be brought in state or federal court. You can pursue

- monetary damages or

- an injunction to stop the improper conduct.

However, you have to overcome the qualified immunity defense in order to recover monetary damages. Note, though, that recent law bars the use of this defense in some cases.

1. What is a Section 1983 lawsuit?

A Section 1983 lawsuit is a civil rights lawsuit. It can be filed by someone whose civil rights have been violated. You can file a lawsuit if the wrongdoer was acting under color of law.1

Civil rights are those guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution or certain federal laws. The Supreme Court recognizes that there is a deprivation of rights when:

- police misconduct such as excessive force and unreasonable use of force (like the use of a taser during an arrest),2

- police officers wantonly search your home and kill their dogs,3

- a judge sexually assaults women while in the course of his/her job,4

- state officials strip welfare recipients of their benefits,5

- jail guards put an ex-gang member in a prison cell with current gang members, even after being told of the danger.6

Rights guaranteed by state law cannot be the basis of a Section 1983 lawsuit. Only federal rights are protected by the statute.7

1.1. How it works

Technically, Section 1983 is nothing more than a procedural device based on a federal statute. It gives federal courts jurisdiction to hear civil rights actions.

No one can be liable under Section 1983. Instead, it creates liability for violating other federal laws. That is why 1983 cases always include an alleged violation of another law, such as the:

- First Amendment (freedom of speech, religion, and the press),

- Fourth Amendment (for example, arrests without probable cause, unreasonable searches),8

- Eighth Amendment (freedom from cruel and unusual punishment),9

- Fourteenth Amendment (for example, lack of due process, equal protection), or

- Social Security Act.10

A 42 U.S.C. § 1983 lawsuit is a statutory civil rights lawsuit that can be filed by someone whose civil rights have been violated.

At common law, prior to Section 1983, lawsuits against the state and its agents were barred by sovereign immunity. Section 1983 was originally designed to protect slaves who were freed in the Civil War. Southern states passed laws that harassed and intimidated African Americans. Law enforcement officers in the south used their positions to assault victims.

Legislators passed the law as a part of the Civil Rights Act of 1871. This act of Congress allowed black victims to file a lawsuit and recover money damages. That lawsuit could be filed in federal court. The congressional intent was for victims to avoid state court decisions. In state court, the victim would likely have faced a strong bias.

2. What does “under color of law” mean?

The civil rights violation has to be committed “under color of law.” People act under color of any statute when they behave with the apparent authority of the state. While on the job, police department officers and jail guards act under color of state law.11

State officials can act under color of law while they break the law, too. They can violate official policy and still maintain the appearance of state action.12 So long as they have the appearance of state actors, they can be sued.

Example: Acting on their own, 13 uniformed police officers break into a house and arrest a man in front of his family. They hold him at the station for 10 hours before releasing him without charge.13

This means that off-duty police officers can be acting under the color of law. However, there have to be signs that the officer made it seem like he was on the job (acting in “an official capacity”). Factors could include:

- showing a police badge,

- claiming to be a police officer,

- brandishing a gun,

- behaving like a police officer, and

- acting like an arrest was being made.

However, working for the state does not always mean that a person acts under color of law. Some people who technically work for the state cannot act under color of law.

Example: Public defenders cannot act under color of law. Their role is to fight the state’s prosecutions.14

On the other hand, people who do not work for the government can still act under color of law. This can happen if they conspire with government officials to deprive someone of their civil rights.

Example: A businessman works with a corrupt judge to keep a competitor from drilling oil wells.15

Section 1983 litigation claims can be filed by private parties against state and local officials.

3. Who can I sue under Section 1983?

Under Section 1983, you can sue state government and local government officials, including law enforcement officers, who have acted under color of law and have violated your constitutional rights. This can include police officers who have

- used excessive force,

- made an unlawful arrest,

- racially profiled (such as during a traffic stop, stop and frisk, or an arrest),

- engaged in unlawful searches and seizures, or

- violated an individual’s due process or equal protection rights.

Other government officials who can be sued under Section 1983 include

- prison officials,

- probation officers, and

- elected officials.

3.1. Federal officials and private individuals

However, Section 1983 does not normally reach federal officials.16 Federal officials can only be sued under Section 1983 if they act alongside state or local officials.17 When they are acting on their own, federal officials can be sued in a Bivens claim instead. (See our article on Bivens vs 1983).

Private individuals can also be sued if they conspire with state officials. This would make them act under color of law.18

3.2. Municipalities

When the constitutional violation was a custom or policy of the municipality, the municipality can be sued, too.19 Municipalities include:

- towns,

- villages,

- cities,

- counties, and

- any municipal program or department, like a school board or public transit service.

However, states like California or Texas cannot be sued in a Section 1983 claim.20

4. Can you bring a 1983 claim in state court?

If you suffered deprivation of any rights, you can file a Section 1983 cause of action in state lower courts (district courts).21 However, the ability to recover monetary damages is drastically reduced. The state official cannot be sued for official conduct for money damages.22

5. What damages can I obtain?

If you are successful in a Section 1983 lawsuit, you may be awarded compensatory damages. These are intended to compensate you for any harm or injury you suffered as a result of the government official’s actions. These damages can include

- medical expenses,

- lost wages,

- pain and suffering, and

- emotional distress.

You may also be entitled to attorney fees and costs. This means that the government will be required to pay for your legal fees and expenses incurred in bringing the lawsuit.

5.1. Punitive damages

In some cases, you can also get punitive damages, which are designed to punish the government official for their misconduct and to deter them and others from engaging in similar behavior in the future.

Punitive damages are generally only awarded in cases where the official’s conduct was particularly egregious. Plus they cannot be recovered from a municipality.23

5.2. Injunctive relief

Section 1983 causes of action can also pursue prospective relief. This comes in the form of an injunction, or court order. That order changes be made to prevent another, similar violation from happening in the future.

6. What about immunity from prosecution?

Some state officials are absolutely immune to 1983 claims for monetary damages. This absolute immunity applies to their official conduct. These people include:

- prosecutors,24

- judges,25 and

- state lawmakers.26

6.1. Qualified immunity

Section 1983 claims that demand damages are also susceptible to the qualified immunity defense. This defense allows other state officials to claim they were acting in good faith. The defense can succeed so long as they did not:

- violate your civil rights, and

- those rights were so clearly established that a reasonable officer would have known their conduct was a violation.27

However, municipalities cannot make use of the qualified immunity defense. They can be held liable even if they did not know they were violating your constitutional rights.28

7. Is there a statute of limitations?

There is a statute of limitations for suing on Section 1983 claims. This means the civil action (lawsuit) must be filed within a certain time frame. However, that length of time depends on the type of constitutional violation.

Courts have to apply the statute of limitations that is most similar to the violation.29 This is often a personal injury statute of limitations, which tends to be 3 years. However, some 1983 cases can have different time constraints.

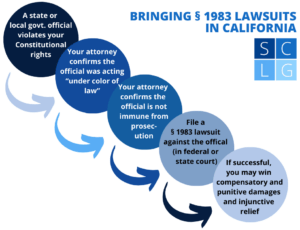

8. What about bringing Section 1983 lawsuits in California?

In California, you can bring a Section 1983 lawsuit in either state or federal court. Opting for a state court can be strategic, especially considering local juries might be more sympathetic to claims of civil rights abuses. However, the monetary recovery may be more limited in state courts.

In California, you can also sue under the Tom Bane Civil Rights Act, which offers a separate, state-specific avenue if any government employees interfered with your constitutional rights by threat, intimidation, or coercion. Utilizing both Section 1983 and the Bane Act can bolster your case, potentially increasing the chances of a favorable outcome.

Note also that recent California law Senate Bill 2 bars police officers from raising a qualified immunity defense in Bane Act lawsuits. Senate Bill 2 also prohibits prison guards and their employers from using a qualified immunity defense in cases where they injured a prisoner or failed to provide them with medical care.

Additional resources

For more in-depth information, refer to these scholarly articles:

- Section 1983 Civil Liability against Prison Officials and Dentists for Delaying Dental Care – Criminal Justice Policy Review.

- The Qualified Immunity Litigation Machine: Eviscerating the Anti-Racist Heart of Sec. 1983, Weaponizing Interlocutory Appeal, and the Routine of Police Violence against Black Lives – Denver Law Review.

- Economic Rights, Implied Constitutional Actions, and the Scope of Section 1983 – Georgetown Law Journal.

- Civil Rights Plaintiffs and John Doe Defendants: A Study in Section 1983 Procedure – Cardozo Law Review.

- Police Consent Decrees and Section 1983 Civil Rights Litigation – Criminology & Public Policy.

Legal References:

- See for example, Gonzaga University v. Doe, (2002) 536 U.S. 273; see 42 United States Code 1983 (Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress, except that in any action brought against a judicial officer for an act or omission taken in such officer’s judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or declaratory relief was unavailable. For the purposes of this section, any Act of Congress applicable exclusively to the District of Columbia shall be considered to be a stat. of the District of Columbia.) See also Chisholm v. Georgia (1793) 2 U.S. 419, which prompted Congress to pass the 11th Amendment. Note that Monroe v. Pape (1961) 365 US 167 established that section 1983 was meant to offer remedies when state law was not equipped to. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal to discriminate with regard to employment, voting, education, public accommodations on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Then Monell v. Department of Social Services of the City of New York (1978) 436 US 658 allowed plaintiffs to use section 1983 to sue municipal entities.

- Bryan v. MacPherson, (9th Cir. 2010) 630 F.3d 805. See also Rivas-Villegas v. Cortesluna (2021) 142 S. Ct. 4. See also California Penal Code 147 PC – Inhumanity to prisoners. Note that failure to give Miranda warnings is not grounds for a § 1983 claim because it does not qualify as violating the Constitution. Vega v. Tekoh (2022) 597 U.S. __ .

- San Jose Charter of the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club v. City of San Jose, (9th Cir. Court of Appeals, 2005) 402 F.3d 963.

- U.S. v. Lanier, (1997) 520 U.S. 259.

- Maine v. Thiboutot, (1980) 448 U.S. 1, 100 S. Ct. 2502.

- Cortez v. County of Los Angeles, (9th Cir. 2002) 294 F.3d 1186.

- Maine v. Thiboutot, Supra. In addition, see Estate of Fritz ex rel. Fritz v. Hennigar, (8th Cir., 2021) 2021 U.S. App. LEXIS 36124; Garrett v. Murphy, (3d Cir., 2021) U.S. App. LEXIS 32385. Savarese v. City of New York, (S.D.N.Y., 2021) U.S. Dist. LEXIS 124390. Gray v. White, (5th Cir., 2021) U.S. App. LEXIS 34119.

- Bryan v. MacPherson, Supra.

- Cortez v. County of Los Angeles, Supra.

- Maine v. Thiboutot, Supra.

- Screws v. United States, (1945) 325 U.S. 91; West v. Atkins, (1988) 487 U.S. 42, 49.

- Home Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Los Angeles, (1913) 227 U.S. 278. See also Ray v. City of Los Angeles (9th Cir. 2019) 935 F.3d 703.

- See Monroe v. Pape, (1961) 365 U.S. 167.

- Polk County v. Dodson, (1981) 454 U.S. 312.

- Dennis v. Sparks, (1980) 449 U.S. 24.

- Wheeldin v. Wheeler, (1963) 373 U.S. 647.

- Tongol v. Usery, (9th Cir. 1979) 601 F.2d 1091.

- Dennis v. Sparks, Supra; Bivens claims (a.k.a. Bivens action) under Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics, (1971) 403 U.S. 388; see also Roberts v. City of Fairbanks, (9th Cir. 2020) 947 F.3d 1191.

- Monell v. Department of Social Services of the City of New York, (1978) 436 U.S. 658 (re. municipal liability.)

- The Eleventh Amendment prevents states from being sued in federal court. Will v. Michigan Dep’t of State Police 491 U.S. 58 (1989) decided that states are not considered a “person” that can be sued under Section 1983, blocking lawsuits in state court.

- Maine v. Thiboutot, Supra.

- Will v. Michigan Department of State Police, Supra.

- City of Newport v. Fact Concerts, (1981) 453 U.S. 247.

- Imbler v. Pachtman, (U.S. Supreme Court, 1976) 424 U.S. 409; 42 U.S. Code § 1983 (“In any action brought against a judicial officer for an act or omission taken in such officer’s judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or declaratory relief was unavailable.”).

- Stump v. Sparkman, (1978) 435 U.S. 349.

- Tenney v. Brandhove, (1951) 341 U.S. 367.

- Harlow v. Fitzgerald, (1982) 457 U.S. 800.

- Owen v. City of Independence, (1980) 445 U.S. 622.

- Owens v. Okure, (1989) 488 U.S. 235.