An extradition warrant allows police to arrest someone who is a fugitive in one state, such as California, but then fled to another state. If arrested elsewhere, the suspect will be extradited back to California to face charges.

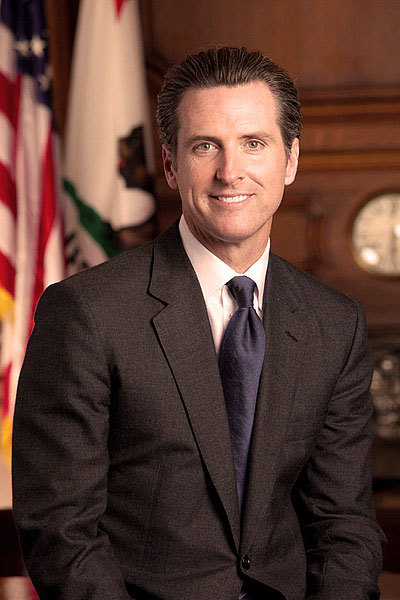

California’s governor issues an extradition warrant after receiving an application to extradite. “Extradition” itself refers to the legal process of transporting suspected or convicted criminals from one state to another.

Note that California extradition warrants – also called a governor’s warrant – can be used if a person allegedly committed a:

In this article, our California criminal defense attorneys will highlight the following about the extradition process:

- 1. What is an extradition warrant?

- 2. How is an extradition warrant issued?

- 3. Can a warrant be issued for a misdemeanor?

- 4. Can a warrant be issued for a probation violation?

A state governor is the only person that can issue an extradition warrant.

1. What is an extradition warrant?

An extradition warrant is a warrant issued for the arrest of a fugitive.

A person becomes a fugitive when he/she leaves California because:

- He/she committed a crime,

- the person escaped from county jail or state prison, or

- he/she violated the terms of probation, bail, or parole.1

An extradition warrant authorizes law enforcement officers to:

- arrest a fugitive, and

- do so at any time and any place where they find the fugitive.2

The “asylum state” (also called “arresting state”) is the state where the fugitive is found. A “demanding state” (also called “home state”) is the state that wants the fugitive returned.

Upon arrest, the fugitive must appear before a judge. This appearance is often called an “extradition hearing” (also called a probable cause hearing). A judge must hold this hearing before agents hand the fugitive over to California.3

Two common grounds for fighting extradition are:

- the extradition paperwork is invalid and does not reflect proper procedures; or

- the police arrested the wrong person (“the identity defense”).

The purpose of the extradition hearing is only whether the asylum state can lawfully extradite the fugitive, not whether the fugitive committed the underlying criminal charges. Only the home state can try the fugitive on the underlying criminal charges.

Any state can be a demanding state. This means states other than California may issue an extradition warrant.

Example: Jerome assaults his ex-girlfriend with a deadly weapon, a crime per Penal Code 245a1. Scared of an arrest, he leaves California and travels to Nevada. California’s governor issues an extradition warrant for Jerome’s arrest.

Here, California is the demanding state. Nevada is the asylum state. Authorities now have the right to arrest Jerome anywhere they find him in Nevada.

Note that Nevada could have issued the warrant if Jerome committed the assault in that state and then fled to California.

The asylum state usually keeps fugitives in custody pending the results of the extradition hearing, which can take 30 days or longer. But in some cases, it may be possible to overcome this presumption and get released on “bail pending extradition”. Or if the home state agrees, the asylum state can release the fugitive if the fugitive agrees to travel to the home state and self-surrender there.

Fugitives who are arrested have the choice not to fight extradition. This “waiver” typically results in the defendant being transferred to the home state right away. (Though if the home state waits too long to pick up the fugitive and the statutory deadline passes, the court would then release the fugitive from custody.)

A criminal defense attorney can help defendants determine whether it makes sense to fight extradition.

2. How is an extradition warrant issued?

A state governor is the only person that can issue an extradition warrant. This is the law per:

- the Uniform Criminal Extradition Act, and

- the Uniform Extradition and Rendition Act.

A governor may issue a warrant after receiving a valid application to extradite.

A California prosecutor is the person that submits this application. The prosecutor does this after deciding he/she wants to extradite.

There are four types of applications under California law. These are:

- one that seeks the return of a fugitive who has been charged with a crime,

- one that seeks the return of a fugitive who has escaped confinement,

- one that seeks return because a fugitive violated his/her bail, probation or parole, and

- one that seeks the return of a mentally ill fugitive.

California’s governor will issue an extradition warrant if the governor:

- agrees with the district attorney, and

- approves the district attorney’s application.

If the governor disagrees, then no warrant gets issued.4

3. Can a warrant be issued for a misdemeanor?

A governor can issue an extradition warrant for a fugitive that committed a misdemeanor. The governor, though, is not obligated to do so.5

Extradition is not mandatory. There is nothing in the Constitution or in California law that requires extradition.

It is a decision that is within the demanding state’s discretion.

Also note that extradition is a lengthy and costly process. For these reasons, it is not sought in every case.

There are several factors a governor considers in deciding on extradition. These factors apply no matter if a fugitive committed a:

- felony,

- misdemeanor, or

- violation of probation, bail, or parole.

Some of these factors include:

- the circumstances, nature and severity of the alleged crime,

- the fugitive’s criminal history, and

- whether there is still sufficient evidence to secure a conviction.

The key question that gets asked is:

“Is it worth California’s time, money, and resources to extradite the fugitive?”

4. Can a warrant be issued for a probation violation?

A warrant may be issued for a violation of:

- probation,

- bail, or

- parole.

Again, note that a governor is not obligated to issue an extradition warrant for these violations.

A governor will consider the following factors before doing so:

- the circumstances, nature and severity of the alleged offense,

- the fugitive’s criminal history, and

- whether there is still sufficient evidence to secure a conviction.

As to the last point, note that some cases involve a significant amount of time between:

- a crime, and

- the date a warrant is sought.

In these cases, a governor may decide not to extradite because:

- witnesses can no longer be found,

- physical evidence was destroyed, or

- experts can no longer testify with certainty.

Legal References

- California Penal Code sections 1547 – 1558. See, for example: Pacileo v. Walker (1980), 446 U.S. 1307, 100 S. Ct. 1633, 64 L. Ed. 2d 221; Morgan v. Horrall (9th Cir. Cal., 1949), 175 F.2d 404.

- PC 1551.

- PC 1554.3; PC 1555.2.

- PC 1549.2.

- See also In re. Baird (1957) 150 Cal. App. 2d 561.